For Kian

for all past and future literary adventures

and for all the tenderness

What would you say if you could speak in a language other than the language of fluorescence? If, alongside a thousand of your clones, you could arrange yourselves into a single word, would it be “Food!”, “Yawn!”, “Help!”? Or perhaps simply, “Hi!”? Sometimes I ask you—or rather, myself—these questions as I gaze at you through the microscope. I just provided you with billions of molecules that, in humans, regulate sensations of pain, pleasure, and satisfaction. Are you, in any way, closer to feeling happiness? Would you now say, “Bliss!”?

My thoughts drift away from the world of cells. I now think about the pain and satisfaction that lie ahead in a few hours on the summit of Mount Whitney. I must look absurd with a lab coat draped over my running and climbing gear, but there won’t be time to change before hitting the trail. Sunrise waits for no one. Just a touch of the early November snow on Tioga Pass closed my road to Whitney last week. Tonight might be my last chance to greet the day from the highest peak in the contiguous States before winter takes hold.

As I leave the lab, I notice light in my good friend’s office. Curiously, the more I wander through the mountains, the less certain I am of my returns, so I step in to say goodbye with more warmth than usual. I lay out my plan, just in case I won’t check in the next day. “Make sure to write down your flow, just like you did after your last summiting,” my friend says, enveloping me tenderly with his expansive arms.

I arrive at the base of Whitney just before two in the morning. The sky is clear, but tonight I ignore the stars. Last time, I looked for the falling ones. Tonight, my focus is on a single star, one that will appear at a precisely determined place and time. I am struck by how different these phenomena are: how random and insignificant the burning of a rocky fragment in Earth’s atmosphere is, and how orderly and far-reaching the regular rise of a massive ball of gas can be.

I set off, half-walking, half-running. The air is deceptively warm. It feels comfortable, but deep in my bones, I know that on the ridge I’ll end up wearing every layer I have. I regularly pass groups that started earlier than me. With each, I try to exchange a few words, gauge their moods, give a verbal high-five, or offer some encouragement. I save myself from bouts of drowsiness by plunging my face into icy streams or snow.

As I reach the ridge, dawn begins to break. It’s my fourth time here, and once again, the sudden view of Sequoia National Park steals the thin air from my lungs. I no longer need my headlamp to see the sign informing me that two miles remain to the summit. I glance at my watch and know I won’t make it in time. Still, I quicken my pace on the challenging, rocky trail. The view to the east peeks through the gaps between granite spires. In one of the openings, the rock suddenly changes color, revealing its direct encounter with the sun. Carefully, I climb onto a narrow ledge to meet the sun myself.

A huge drop beneath my feet presses me into the cold wall behind my back. The sun is still too sleepy to blind me, so I stare directly into its face. I try to distill the moment into three lines of haiku, but another thought distracts me. I remember that photons, carrying relativistic momentum, exert radiation pressure. The effect is, of course, negligible, but the amplifier of imagination works flawlessly. I imagine the sun’s rays pressing me into the granite, and I feel steadier. Calm replaces fear, and the moment slips away from words.

Stillness brings cold, and cold brings reality. I return to the trail to tackle the final mile. Completing it for the fourth time reinforces my sense that there’s a certain blandness to it. Perhaps its “flavor” is stolen by the dragging anticipation of the summit. At last, among thousands of slabs and boulders, a shape emerges—one that nature could not have formed. I peer inside the small, stone hut. I walk around it, finding no sign of life. Such solitude is not common on the summit of Whitney, and in it, I find a melancholic charm.

I write my name and a few comments in the summit register. From my pouch, I take out a ginger chew. This is a chew with a history, and I leave its next chapter in the hands of those I passed on the trail. Someone might say ginger chews are fungible, but not this one. This one has climbed Mount Whitney twice. It has been to the Burning Man festival and traveled through Europe. It was once called an emergency chew, so perhaps its place is here, on the summit of Whitney. Perhaps it will help someone in need. Perhaps a gale will carry it away. Perhaps tales will arise about its travels. It is a chew with a past and a future, which makes it non-fungible. I taste bitterness in my mouth—a prelude to a cynical thought. I feel the cold, and with it, cold thoughts begin to seep into my mind. At the last moment, before the thought fully crystallizes, I put on my down jacket, and the bitterness disappears.

I look south, toward Mount Russell. Three months ago, I stood there, gazing at Whitney. Back then, I stretched an invisible thread between the two peaks. The autumn winds have since blown it away, and now there is no one on the other side to stretch it again. I turn east, to the sun, now comfortably settled above the Alabama Hills. In the distance, I spot Telescope Peak, the highest mountain in Death Valley. If I had a telescope, I would see a few familiar faces there today, and one very familiar smile. But a thread that could reach that far would weigh too much to carry up any mountain.

I sit on boulders arranged like a bench. I eat a few fungible ginger chews and think again about the special one. Did it weigh more than that impossibly heavy thread? How does one weigh a symbol? How much does a symbolic act or a ceremony matter? The rugged landscape and my “offering” to the mountains remind me of Sherpas, who would never ascend the Himalayan peaks without the puja ceremony. I hear the flutter of prayer flags in five colors, representing the five elements. Each one bears a lung ta, the wind horse, symbolizing the transformation of bad fortune into the good one. Everywhere, symbols pile up, layer upon layer.

In my world, there is no god. No eye gazes at me through a cosmic microscope. No one asks what I would say if I could speak the language of angels. Yet this does not imply the absence of the sacred. I once read about sacredness without god in Mircea Eliade, but it is only here, on the summit of Whitney, that it strikes me to the core. Our need for the sacred—the need to make objects and places special, to transform them into symbols—may be buried deeper than, for example, the natural need for connection with other people, but it resides just as naturally within most of us.

Gazing into the expanse before me, I gaze into the expanse within myself. I try to understand the nature of my need for the sacred. I wonder if my internal, dynamic system of symbols, despite its areligiosity, is beginning to verge on piousness. Is it buckling under its own weight? On the back of my hand, I notice a symbolic sun, drawn a few days ago by a kind soul for a lucky journey. I had forgotten about it, though just yesterday I was careful not to smudge it. This forgetfulness makes me realize that my symbolism isn’t entirely serious. It stems more from a need to ornament things and events with a particular kind of fleeting, and in that sense, light, beauty. Today’s journey to Whitney would (and will) be recorded in my memories one way or another. The symbolic chew is a stylistic flourish, a poetic metaphor that embellishes that record. I title this reflection “Symbol and the Sacred as an Autobiographical Stylistic Device” and file it away in the drawer of memory.

Gazing into the expanse within myself, I gaze into the expanse before me. I hold onto this view—sharing it with no one, not even my phone. As a greeting-farewell for my absent god, I arrange the word “Hye!” from small stones and follow my footsteps back to the car. I reach it before noon, take a potent dose of caffeine, and without delay, drive off toward the Alabama Hills.

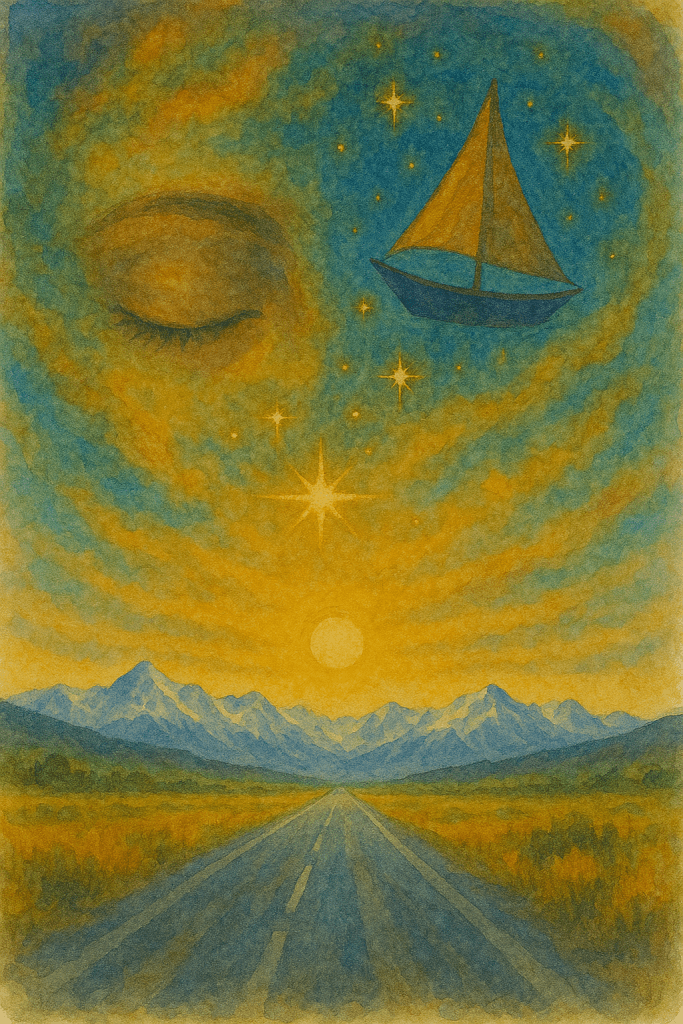

I drove this road a few months ago. Fatigue and drowsiness tangle time and circumstances. I fight against my heavy eyelids. From the right, an absent pair of eyes looks at me. For a split second, the brightness of all the stars radiating from them outshines the sun, now at its zenith. Sometimes, someone’s eyes open for you, just for a moment. In their light, you see things more clearly, you resolve paradoxes. Then the eyes close, and the paradoxes return, taking away your sleep. “I need to sleep so badly,” I think, as I watch a massive sailboat glide across the sky. It is pushed by the relativistic afterglow of those absent, now-closed eyes. That sailboat is me.

The right wheel drifts onto the shoulder. I wake up and swerve back just in time. The sailboat sinks in a sea of adrenaline. I stop the car and step outside. I slow my breath and take in my surroundings, now fully awake. The last time I stood here in summer, everything was green. Now, fall glows brightly under the light of a single star. Both versions are beautiful.

I recall the suggestion from my friend with expansive, tender arms. I can see a clear narrative arc connecting that summer to this fall. I draw the bowstring tight across this arc and feel ready to release volleys of words like the volleys of stars from a few moons ago. I get back behind the wheel, switch on my phone recorder, and:

What would you say if you could speak…