The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they sing. They just screech in pain.

Werner Herzog on the set of Fitzcarraldo

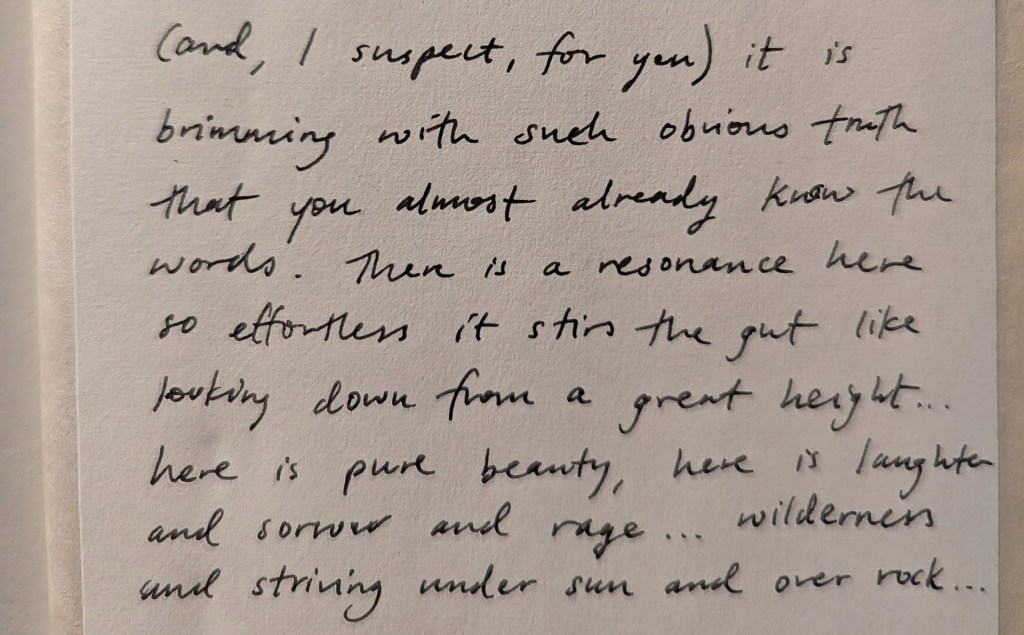

Some paragraphs in Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire I read over and over—out of awe, out of envy, and out of eagerness. Every word feels exactly where it should be. Or maybe it’s not that every word is perfectly placed, but that every plant he describes, every rock, every shadow and gust of wind is simply there, where it belongs. It’s not about Abbey’s literary perfection, but the perfection of the desert itself. Maybe. Or maybe, as a friend wrote in the dedication of the copy he gave me, it is brimming with such obvious truth that you almost already know the words. Maybe when you observe something long enough and closely enough, there is only one truth—and that truth dictates the order of words.

A dot from an “i” begins to slowly slide down the book’s page.

“How romantic, living in books,” I think, watching a tiny insect—a booklouse—meander among the ascenders and curves of the letters. But then the truth reveals itself, and it dictates the next thoughts. What does a booklouse feed on? Glue and mold—suddenly, less romantic. And what feeds on booklice? Monstrous, machine-like killers—pseudoscorpions, spiders, predatory mites. Other mites hunt those mites. And something hunts them too. You may be holding a romance in your hands, but between its pages, there’s a horror story playing out.

It’s May, and the mountains outside my office window are greening, timidly and freshly. The first grasses sprout from the ashes of the great fire half a year ago.

“Spring. New life. Some landscapes heal the way wounds do,” I smile reflexively, looking up from my screen. But again, the truth reveals itself, and it dictates the next thoughts. This isn’t healing. It’s a relentless battle—for light, water, minerals. A race against time before summer and fall, with their slow-burning fire of drought and heat, turn abundance into compost and dust. It’s growth and death. Life growing on life. As if the tissues of a healing wound were themselves cancer. And the cancer, in turn, was dying of cancer. You can see an idyllic scene in a landscape—but what’s actually happening is a drama.

The smile doesn’t leave my face. There’s more beauty in this truth than in the banal “Spring and new life.” The same truth lives in the mountain slopes and in the crevices between book pages. And the same truth applies to us. How could it not? We resist it by building heated houses, purifying our water, taking antibiotics, and so on, and so on—but in the end, each of us succumbs to it. Like the grass. Like the booklouse.

The only difference is, we get to read the books we live among. And write them.

But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it. I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgement

Werner Herzog